Authors:

(1) Matthew Sprintson

(2) Edward Oughton

Table of Links

2. Literature Review

2.1 Reviewing Broadband Infrastructure’s Impact on the Economy

2.2 Previous Research into IO Modeling of Broadband Investment

2.3 Context of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act through Previous Research

3. Methods and 3.1 Leontief Input-Output (IO) Modeling

3.2 Ghosh Supply-Side Assessment Methods for Infrastructure

4.2 What are the GDP impacts of the three funding programs within the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law?

5. Discussion

5.2 What are the GDP impacts of the three funding programs within the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law?

5.3 How are supply chain linkages affected by allocations from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law?"

Acknowledgements and References

2.3 Context of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Act through Previous Research

Policy choices can help maneuver broadband networks to achieve more positive outcomes (Oughton et al., 2023; Oughton, 2023), but efforts to close broadband gaps have not yet managed to do so (King & Gonzales, 2023). Currently, only 77% of people in the United States subscribe to a broadband connection (Pew Research Center, 2021). Many unconnected Americans lack access because of connection prices, insufficient technology, scarce information, and inadequate government policies (Bauer, 2023; Oughton et al., 2022; Rosston & Wallsten, 2020). A significant divide exists between urbanization and income levels in US households (Rothschild, 2019). For example, with 82% of urban households having a fixed broadband connection, only about 70% of rural areas have the same connection available (Li et al., 2023; United States Census Bureau, 2021).

Most Native Americans living in tribal areas do not have access to the same broadband infrastructure that other communities have. There are numerous reasons - progress is hampered by a lack of trust, social structure, limited resources, and insufficient education (Korostelina & Barrett, 2023). Government investment could lead to increases in broadband connectivity, but substantial disparities still prevail (Andres et al., 2024; Healy et al., 2022). For example, 55.6% of Native American tracts have seen an expansion in broadband providers between 2004 and 2014, with 27.7% of Native American tracts now having an above-average number of providers (Mack et al., 2022). However, the percentage of Native households with Internet access is still 21% lower than in the surrounding areas (Bauer et al., 2022). For the US government to ensure everyone can participate in a modern online economy, there needs to be more infrastructure built to support tribal broadband and investment in education and awareness (Duarte et al., 2021; Hudson et al., 2021; Mack et al., 2023).

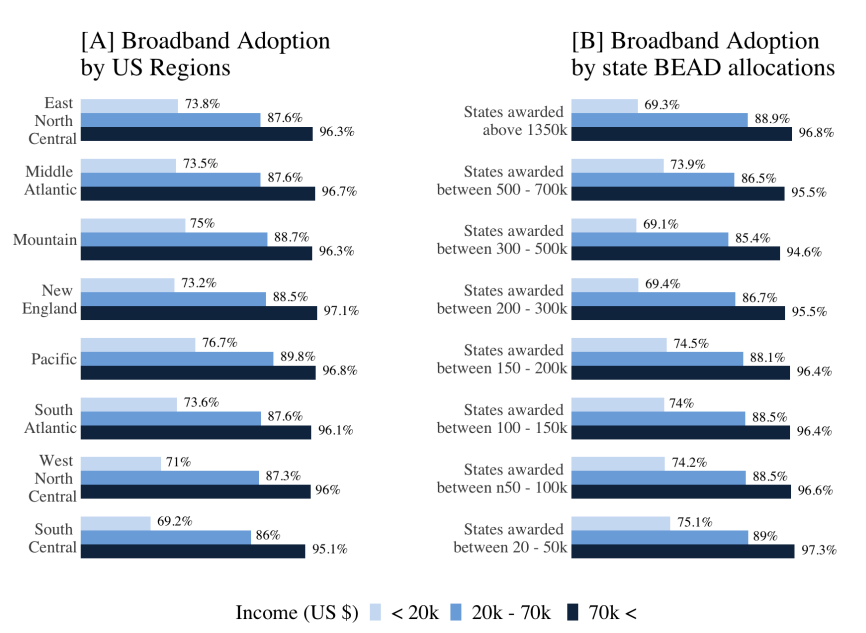

As found in previous studies, Figure 1 emphasizes empirically the association between broadband inequality and income level (Deng et al., 2023; Houngbonon & Liang, 2020; Wolfson et al., 2017). This problem is exacerbated as broadband adoption has been found to increase wages and hiring in a community (Poliquin, 2021; Yin & Choi, 2023). Thus, communities with reliable broadband connectivity often have higher earnings and more opportunities, aggravating the inequality shown in the figure (Consoli et al., 2023; Mathews & Ali, 2023). Figure 1 (A) shows that, on average, communities with a mean income of less than $20,000 have poorer access to broadband than wealthier communities. This can constrain economic opportunities in poorer areas, meaning citizens in these areas are disadvantaged in seeking new employment options and adapting to changing labor markets. Figure 1 (B) shows us that the disparities in connectivity, separated by income, are present when we compare regions with larger broadband allocations. 69.3% of those making under US $20k in states receiving over US $1,350 have access, whereas 75.1% have access in states receiving less than US $50k.

Finally, 20.9% of Tribal lands still lack access to reliable broadband (Hutto & Wheeler, 2023). The adverse effects of the lack of reliable broadband were shown throughout the COVID-19 pandemic when many tribal communities were restricted from accessing schools and working opportunities because they did not have a reliable connection to broadband infrastructure (Kroll, 2023; Le-Morawa et al., 2023; Levin et al., 2023). Broadband connectivity can be efficiently implemented through inter-tribal communication throughout the community and community-specific broadband dissemination (Gellman et al., 2021). The Tribal Connectivity Program’s awards aim to support the deployment of required broadband infrastructure by working in tandem with affected communities (Tribal Broadband Connectivity Program, 2023).

Now that a thorough literature review has been undertaken, the methods for analysis will be presented.

This paper is available on arxiv under CC0 1.0 DEED license.